Challenge, Part 2: See Image

I bet you’ve been positively climbing up the walls to see the continuation of my previous post on challenge in game design. It’s been an unclosed loop, a loose end, a DREAM of yours yet unfulfilled. Don’t worry, I’m here to help. Aye, the supposed rub: You can’t design an extremely challenging game without it being frustrating.

Conclusion: FALSE

The main question that begs answering here is this: which design features lend themselves to motivating challenge versus frustrating challenge? How can we create a challenging experience that players want to come back to again and again?

I would like to present the humble idea that the “blame game” is the main factor in how challenge is interpreted by the player, and how difficulty translates to motivation or frustration.

“The Blame Game, you say? That sounds like a bad ’90s sitcom.” Yes, yes, I know. Sorry about that. (Not really.) For you avid game players out there, imagine times where a game was intensely challenging but in a way that motivates you to play it more. I’d bet you a (delicious bowl of stewed rabbit for carnivores / hummus-related dish for you veggie-inclined folks) that you didn’t blame the game for your failures, you blamed yourself.

I’ll explain using a thoroughly absurd example: Mario Frustration. Try not to go away for too long, it’s lonely in here.

Pay close attention to the commentator as the video begins. What’s the first thing he says when he starts the level?

What the fuck? There’s no floor?

Immediately, the challenge is pinned on the game itself, and not on the player. The blame game has begun! If the game was designed properly then the commentator would have said something akin to “I can’t believe I wasn’t able to figure out how to avoid that.” (If only the designer had tried harder, such a shame…)

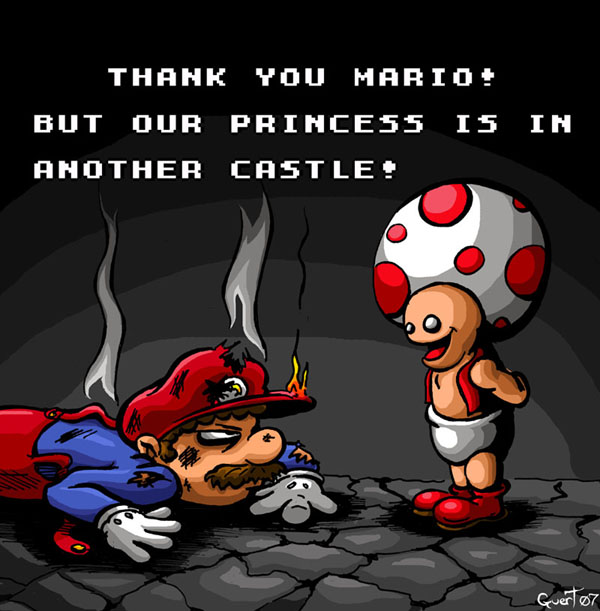

Another beautiful example of what creates frustrating challenge in the video is about a minute in. Go watch it if you haven’t already.

Do you feel the player’s urge to throw something? He just accomplished an amazing feat, only for his success to be taken from him and stamped on. This is a case where no amount of player skill could have prevented the death – truly a “Learn by Death” situation from Part 1. No entity except the game could possibly be blamed.

Why is the blame game so important? This goes back to a psychological concept called the “locus of control.” Basically, the locus of control is the extent to which somebody believes they can control events that affect them. In this case, the extent to which game players can affect the outcome of a pass/fail challenge. (Either through enhanced focus, better strategy, or practice.) If somebody believes that they can control the outcome based on their own actions, they are referred to as having an internal locus of control. If they feel that the outcome is mostly controlled by fate or chance then they are said to have an external locus of control.

Substantial research has been done on people with external vs. internal loci of control. Multiple studies have shown that as the locus of control becomes more external, the reaction to frustration becomes less constructive and more punitive. For game design purposes, a punitive response to frustration could mean the player stopping play or never playing the game again. A constructive response could include the player thinking more about how he could surmount the challenge, then continuing to play. Another study correlated an external locus of control with increased aggression in response to frustration.

What can the designer do?

- The player must feel prepared

Difficulty curves are especially important: if a player is convinced that the game is progressing unfairly, he will blame the game. Portal is an excellent example of a game that has a well designed difficulty curve. The designers use an “acquire, test, master” model throughout the entire game. For every new game skill that the player must learn to progress, the game presents its use to the player without the player having to do anything at all. For example, even before you wield the Portal Gun itself, the player gets an opportunity to walk through Portals that are part of the level design to see how they work without having to make use of them immediately. Once the player understands what the portals are good for, the game then tests the player’s knowledge using simple puzzles. Finally, the difficulty level builds in a gradual manner until the player feels he has mastered the portal mechanic. This same idea permeates every other mechanic in the game.

- The challenge must appear to be doable

Remember that appearances count for a lot. Even if something isn’t extremely hard, if it appears that way the player will take that to heart and blame the game for his failures. If the challenge appears to be too challenging for the player to accomplish, he will become demoralized and might not even want to attempt the challenge.

- The game should adjust if the challenge is too great

As a last resort, make sure the game is flexible enough to account for challenges that are too hard to beat. A covert, sliding difficulty scale can be a useful tool to keep arousal levels up if the player continues to fail. A player will be much more likely to continue playing if he grows ever more tantalizingly close to succeeding. However, if this scale is made to be too obvious, that may sap the feeling of accomplishment from the player. For example, in a fight with 10 enemies the proper sliding scale would be to reduce each of their hit points by 5% on each failure. An improper (yet nearly equivalent) scale would be to eliminate 1 enemy for every failure. In the second case it’s obvious to the player that the game is adjusting to him, which is demoralizing. The game may also allow the player to lower the difficulty level himself as an alternate solution. This can temporarily sap some excitement, but allows the player to get over the frustration hump and continue enjoying the game.

Emily - July 30, 2011 2:07 pm

Do games regularly do that make the enemies easier thing?

Josh - July 31, 2011 12:06 am

It’s rare as far as I know of. More common is level scaling, common in open-world games like Fallout or Elder Scrolls, where enemies that used to be easier are scaled up in difficulty as the player progresses. This is a pretty controversial technique, though, because players never really get to feel like they are making progress. Those mutant wolves you fought off valiantly early in the game? Yep, just as hard as they were in the beginning. This goes back to the bit in my post about not making scaling either way obvious. Personally I don’t find up-scaling to be very useful, but down-scaling can be essential. I’m surprised more games haven’t implemented it.

Pingback: Tidbits: Vindicated! « Synonyms for Fun