Indie Game: The Movie

This is not a movie about games, or really even about making games.

I know, you must be sitting there in your comfortable chair, incredulous with jaw agape that a movie called Indie Game isn’t about games! Bear with me, though. As with all great documentaries, this is a movie about people – and it truly is a great documentary. If you want to see a blow by blow of the story, I highly suggest the Wot I Think review over at Rock Paper Shotgun, purveyors of many fine gaming related words and paragraphs. A warning, though, it’s spoiler-laden! Regardless of your choice to spoil yourself or not, you should listen to the amazing soundtrack while reading to set the mood.

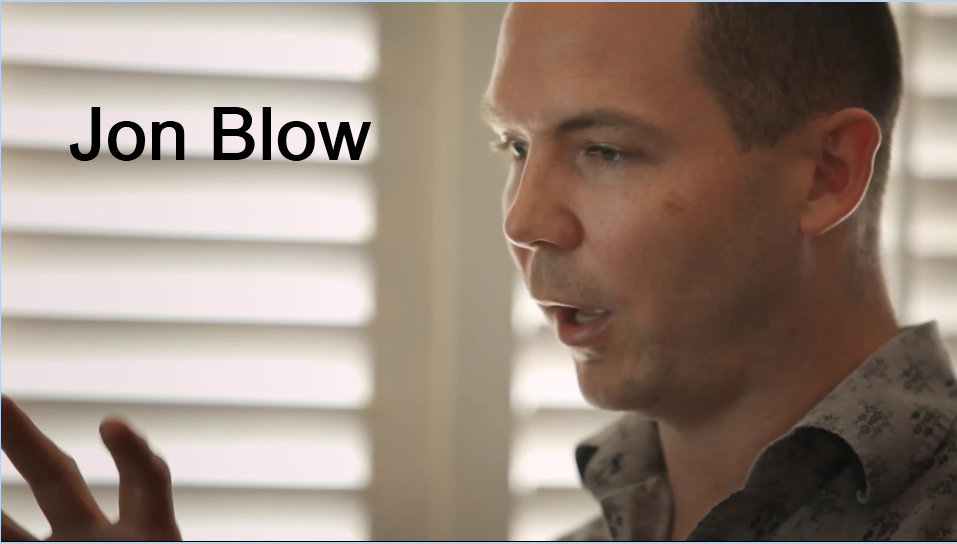

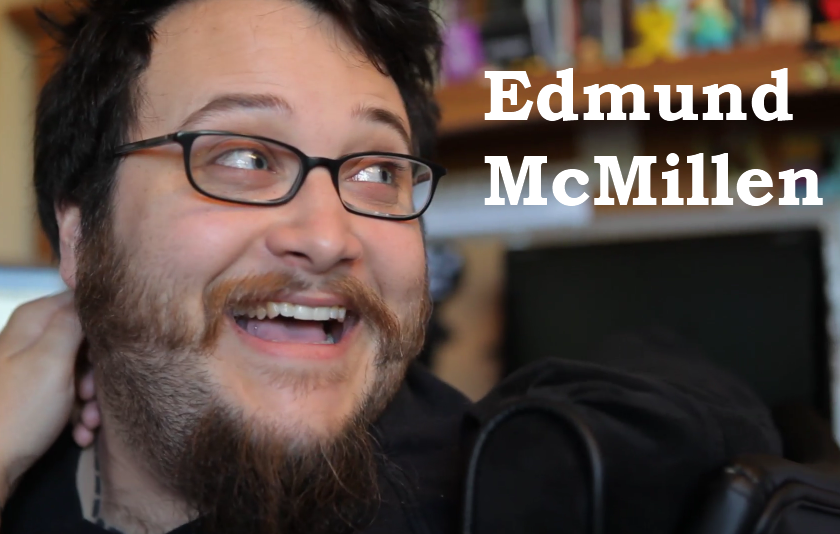

Indie Game follows the lives of four independent game developers: Jon Blow of Braid, Ed McMillen & Tommy Refenes of Super Meat Boy, and Phil Fish of FEZ. Whether they say it directly or not, each of them believes that they are producing something both profound and personal. I’m inclined to agree with them; humans have been making art since the dawn of our species, and video games are as much part of the pantheon of art as any other medium (unless your name happens to be Roger Ebert.)

Art is how we communicate our most profound and complicated feelings in a way others can digest. Art is a means of communicating, of seeing through another’s eyes. According to Tommy of Team Meat: “It’s why a writer writes, I guess. You know, it’s because they can. That’s the most effective way they can express themselves, and a video game is the most effective way I can express myself.” And really, what is expression without somebody to express to? We, the viewer, see not only the story of these games but also the emotions tied up in it all: the fear, the love, the passion, and everything else under the sun. The games are wonderfully different, and so too are their creators; in fact, they act as near-perfect complements to each other.

To me, video games are the ultimate art form. It’s just the ultimate media. I mean, it’s the sum total of every expressive medium of all time, made interactive. Like, how is that not…IT’S AWESOME!

Phil Fish became a developer rock star in 2008, when an early tech demo of FEZ won an art award at the Independent Games Festival, the Woodstock of the indie scene. With this new-found fame also came incapacitating media attention and fan pressure to deliver. From delay to delay, fan opinion turned cynical and Fish gained a healthy reputation for lashing out at his detractors. Fish binges and purges on grandiosity and style, and takes his image very seriously. (This is plainly reflected in his dress, which usually includes a scarf and thick, black Ray-Bans.) More than anything, though, Fish desperately wants to deliver on the promise of FEZ.

Jon Blow is a grizzled game industry veteran who has been almost perpetually unfulfilled with his past work. Braid was an outgrowth of his desire to do something close to his heart, seeing it as a way to emotionally connect with his audience. However, after Braid’s release and subsequent massive success, Blow became almost obsessively defensive over Braid’s intended message. Blow continues to struggle emotionally with the disconnect between his intentions and gamers’ experience.

Ed McMillen and Tommy Refenes are a tag team of developers with a number of games under their belts, but by no means veterans of the industry. Once the crowds saw Super Meat Boy they couldn’t stop talking about it, and now Microsoft has placed a hard deadline on its release or else they won’t get advertisement on Xbox Live Arcade. With no time to spare, they sacrifice just about everything else in their lives to get the game done.

Making [Braid] was about “let me take my deepest flaws and vulnerabilities and put them in the game, and let’s see what happens.”

Personally, I strongly connect with Indie Game because of the similarities between indie game development and grad school. Slow down, slow down, I know that’s a weird statement. For any creative process, whether it’s a dissertation or a game, it’s often fueled by a desire to share something meaningful with others. Ironically, even if it is a journey of connection, it’s also often journey traveled very much alone. In the grad school process, intense personal pressure tends to be the only thing keeping most of us going. For indie devs, though, that same internal pressure is amplified by the vitriol they receive daily from mercuric “fans.” Phil Fish put it best:

I’m working on it as hard as I can, all the time. It’s like “What’s taking so long? What the fuck are you doing, Phil?” (Fish’s eyes are practically bulging out of his head, blown up to poster size by his thick glasses.) “Fuck off! … It really gets to me, I guess.”

Juxtaposed against the isolation of creative work, however, are the sources of strength: friends, family, spouses, and true fans. In difficult times, and perhaps even more-so in the face of success, these connections keep the protagonists together, ultimately even redeeming some. The “ache in the stomach” realization of Indie Game, though, is how starkly contrasted the characters’ inner lives are. Some of these guys are just not in a good place emotionally, and it shows. The cinematography serves this point and is sharp as a dagger, which like it or not gets plunged into your gut again and again. People who dislike Indie Game enjoy calling it “First World Problems: The Movie,” but seeing these people struggle with their lifelong passions makes me realize their existential pain feels just as real as physical hurt.

You fucking go crazy when you’re like this. Well, I obviously grew this mustache. It is the reclusive cowboy. I need everybody to know how crazy I feel, on the outside.

If there is any one moment (among many) in Indie Game that must be quoted to sum it all up: Phil Fish has just finished showing off FEZ to a huge audience of people, and reflecting on his feelings, he turns from enigmatic to vulnerable, saying somberly:

You wanna be liked. You wanna be appreciated, you want people to approve of your work. It’s just that, you know, you work on a project for so long like that in semi-secrecy, you can’t really show it, you can’t get that much or any feedback, really. You just want to get any old morsel of appreciation… Well, I do anyway. It’s like when people say “I don’t care what people think about this and that.” It’s like, I care about what people think. I wish I didn’t, but I do. It’s kind of silly, like I’m a little annoyed about how much I care about that stuff. Yeah, I wish I didn’t care that much, it is kind of like I need any bit of feedback and love that I can get.

The entire movie is composed of these cut-to-the-core moments. I must have cried for the last 20 minutes straight. Again: This is not a movie about games.

You kind of have to give up something to have something great, in a way. I’m depressed now because I’m on the brink of something amazingly huge, but it’s a different kind of depression. It’s not a stuck depression, it’s a “oh holy shit” depression. It’s an unknown depression, which is kind of weird. But it’ll fade, because once it’s out, it’s out.

It should be apparent by now that this film is nothing short of an emotional rollercoaster, as hackneyed as that sounds. I was profoundly affected by its message and its immense heart. After all those words, I feel like I should make things simple for you, gamers and non-gamers alike: see this movie, see this movie, see this movie.