Where Do We Go From Here?

In my previous article, I hope that I made it exceedingly clear that working conditions in graduate-level research have gone off the rails. So now, what do we do about it? Where can we go? Are we totally screwed?

No.

Working Regulations and Unionization

The most direct and most obvious option is the regulation of working hours, at least for graduate students in public universities. For the rest, unionization could provide relief.

It may seem inappropriate to regulate the working hours of some graduate students, but the fact is that graduate students are in an awkward position. Whether we are actually employees or not is a serious gray area, and until that is resolved graduate students will be vulnerable to exploitation, because essentially we have ‘fallen between the gaps.’ The National Labor Relations Board is expected to make an important ruling soon on whether graduate students at private universities who receive university stipends can be considered employees rather than students. This will have major ramifications on the ability of graduate students to organize and form unions.

While there is no legal precedent for regulating the working hours of graduate students, let me give you an example of why it might be important for safety reasons in the hard sciences.

I work regularly with Hydrofluoric Acid, one of the most dangerous inorganic acids known. Hydrofluoric Acid is very interesting because exposure does not lead to immediate severe pain. Instead, the acid disassociates; the fluoride ion works its way to your bones, then binding to and leeching away the calcium and magnesium within. Systematic toxicity is rapid and death is likely unless rapid care is saught. Burns that cover one percent of total body surface area have been known to be fatal. If you want to know more, visit here. (Warning, Very Graphic)

I do not take working with this chemical lightly, and neither do my labmates. This is not the only hazardous chemical we work with by any means, either. Under no circumstances should any graduate student in the sciences be forced to work more than a regular working week if they are dealing with potentially lethal chemicals. Surgeons have already had hourly limitations placed on their training and residency periods for safety and sanity reasons. Why not apply this to scientists as well?

Some students are obviously very dedicated to their work, so perhaps a hard cap would be unreasonable. I personally know of many that would scoff at such a thing. However, universities simply having an “expected number of working hours per week” figure on a signed contract would lend significant protection to graduate students. I am not aware whether this is common practice or not, but giving students a simple figure to reference will shore up confidence when facing abusive advisers.

For private universities, unionization is the only option in this category. The main issue with unionization is that graduate student unions are relatively toothless compared to other types. Unions partially rely on the ability to strike if working conditions are inadequate for long periods of time. The ramifications of a graduate student strike would be that the students would delay their graduation and their research, something that no grad wants to do. I’m interested in hearing some other ideas on how graduate unionization could gain the bite they need to function properly.

Letters of Culture

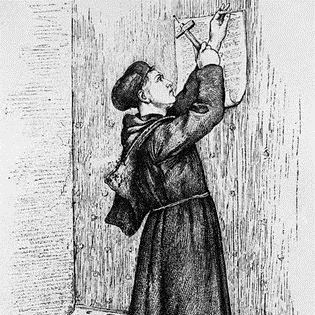

If you read this letter before picking a research group do you think it would influence your decision? I certainly do!

In any competitive marketplace, information is the difference between the market making smart decisions and dumb ones. In our current state, prospective graduate students are largely left in the dark as to the research setting they are getting into, short of tracking down and asking group members directly. This lack of good information makes it vastly more difficult for prospectives to make smart choices. Once they get in and ascertain the culture, it is already too late to switch. Some majors are lucky here in that they allow their graduate students to rotate and then decide, however not everybody is so blessed.

The Council of Graduate Schools could create an opt-in, self-regulated program where PIs write a “letter of culture” that reflects the expectations that they has for the group. It should outline the typical number of hours worked, whether working on weekends is expected or required, how many papers should be published before student graduates, their policy on vacation time, anything else pertinent. Once a student read the letter of culture from a “slave-driver” PI, they would be able to make a much more informed decision. Of course, this doesn’t solve the issue if there are no other groups to join, but at least they know what they are signing up for!

By creating a reliable flow of information to prospectives, groups that demand too much of their students or do not provide a letter of culture will find fewer willing students to do the work. This may place pressure on the group’s PI to reconsider the working conditions that he or she demands.

Reformation of Research Grants

As a percentage of Gross Domestic Product, federal funding of science has been steadily dropping since the mid-60s from about 2% to about 0.8%. As funding levels decrease, competition will only increase. Labs that have a track record already will still be able to get grants, but what about the startups? Only those who are willing to sacrifice themselves and their students on the altar of science will be able to keep up. At what point does the center fall away, though? At what point does the public science infrastructure crumble and the most promising minds sigh and leave? I am not an economist, so I would be interested in hearing some opinions on how the grant system can be changed for the better. Politics is also an important component, so advocacy is the only route to a better future on that side of the coin.

Increase Flexibility of PhD Research

Ph.D students are locked in to their research, and changing direction is next to impossible – there’s no doubt about it. We have students writing monolithic tomes that some compare to marathon runes, which only a select number of people will ever read. These turn into a major roadblock for many Ph.D students, and unnecessarily extends the Ph.D process to a decade and beyond for those unlucky enough to get stuck with an untenable topic. The effect of consolidating a student’s research into a single document is that they cannot be flexible in their research pursuits when things do not go as planned. As I mentioned previously, even if a student were to try to switch to greener pastures, they would find themselves losing years of work.

Some programs allow for students to submit three peer-reviewed research papers rather than one titanic work. Implementing a policy similar to this at more universities would go a long way to restoring students’ sanity. This reform would afford them the flexibility to switch topics, advisers or universities without fearing large amounts of work being lost. It would still be a setback, of course, but with every publication as another notch in the belt, the road to the degree would be simplified greatly. We would find Ph.D’s graduating with less debt (for those who are unfunded), more time to use their degree, and more confidence in the research process.

Disconnect the Adviser from the Committee

This is probably the most radical departure from the current status quo. The role of the adviser in graduate school is to guide a student through his or her studies, into research, and eventually to publishing papers and writing their dissertation. While it may seem intuitively obvious to place the person in charge of the lab or group that the student works for on the committee to allow them to graduate, shouldn’t the student purely be judged on the quality of his or her dissertation. Isn’t there a conflict of interest when the adviser, who wants to squeeze as much work as possible from each student, is on the same committee that allows a student to finish? Is that giving one person too much power? Again, some will argue that in industry it is one’s boss that is largely responsible for promotions. However, it is important to realize that a Ph.D student who cannot graduate is in a much worse position. Essentially they have lost years of work with nothing to show for it, and for some even less than they started with.

Anything else?

This problem is of utmost importance, and cannot be solved by any one method. What are your recommendations for fixing research as we know it? I’m looking forward to hearing from you!

P.S. I posted this using phone-tethered internet on my desktop because our service provider fell off the ball. I hope you understand the dedication here! Good evening.

scooby doo - September 14, 2011 4:41 am

I do not believe that having ‘recommended hours’ or anything of that nature on the contract will do anything. Those who are ‘slave drivers’ will smile at that and say something to the tone of ‘that’s for the other groups.’

Advisors are faculty, faculty want/need teneur, requirement for teneur at a research institution relies heavily on funding/publication record, funding and publication record correlate with quantity/quality of work, quantity taking a head.

As public universities get less funding they are required to find funds elsewhere, and research grants are very lucrative. What’s more, the system has become dependent on these funding sources (in essence exchanging state taxes funds for federal tax funds). As the federal government has concomitantly reduced its research funding, the difference has been made up through the investment in research via private corporations (last I saw, this has almost perfectly balanced the decreased funding via the government).

Funding is everything because job security is everything